Caistor Roman Town

Caistor Roman Town also known as Venta Icenorum, was the largest Roman town in East Anglia. When it was first established in the AD70s, the town was unenclosed. The banks and walls visible today were not built until the 3rd century AD. The town was laid around a grid of streets, and in true Roman fashion, there is evidence of an amphitheatre to the south of the walled area, and a temple to the north-east; this temple was in addition to those in the centre of the town. The town also boasted running water, baths, a town hall (basilica), and a central public place (forum).

The site was still occupied from the early 6th century, during the early part of the Anglo-Saxon period, but the Roman buildings and infrastructure were left to decay. Venta Icenorum was eventually abandoned in the 8th century, when Norwich became the civic centre for the county. It is one of only three Roman towns in the country that were not built over in later centuries, giving us an extraordinary opportunity to explore its below-ground archaeology.

The Roman town site is owned by Norfolk Archaeological Trust

A very professional, methodical and inspiring set up. This work deserves to continue.

Visiting Caistor Roman Town

For more information on visiting the site please visit Norfolk Archaeological Trust’s page on the site – click here.

Tas Valley Landscape Project

To better understand Caistor St Edmund, we need to be able to try and interpret it in the context of the Tas Valley area as a whole. The town sits in an area rich in prehistoric remains and must have been important to humans from long before the Romans arrived. there is the Wood henge at Arminghall and the complex of crop marks around it, barrows excavated along the ridge to the west, and multi-period artefacts in the shape of pottery and flint tools which pre-date the Roman site.

There was a trenchet adze from the first year’s excavation in the town, a prehistoric hand axe, that appeared to have been curated, from one of the other town excavations, numerous Mesolithic finds and an axe from Wymer Field, and flint and pottery scatter from fieldwalking. The area has a deeper history which we are exploring.

There are also interesting sites that post-date the town in lots of forms including deserted and shrunken medieval villages with visible hollow ways around Bixley and Arminghall, a plethora of interesting Georgiana and Victorian buildings, farms and boundaries, some of which date back to Tudor or Medieval times and even earlier. There’s even modern sites of interest such as the remains of a Chain Home Low radar station including a surviving tower at Stoke Holy Cross, remnants of Second World War stop lines in the form of tank obstacles, pill boxes and Home Guard posts, plus a starfish site to drive Luftwaffe bombers away from Norwich, there’s even cold war history in the form of OC sites and dugouts buried in the fields.

It is important to recognise that although Caistor Roman Project started with the Romans the site and history of the area is much deeper and exploring this gives us more context for it’s development and subsequent decline.

To better understand Caistor St Edmund, we need to be able to try and interpret it in the context of the Tas Valley area as a whole. The town sits in an area rich in prehistoric remains and must have been important to humans from long before the Romans arrived. There is the wood henge at Arminghall and the complex of crop marks around it, barrows excavated along the ridge to the west, and multi-period artefacts in the shape of pottery and flint tools which pre-date the Roman site.

There was a trenchet adze from the first year’s excavation in the town, a prehistoric hand axe (that appeared to have been curated) from one of the other town excavations, numerous Mesolithic finds and an axe from Wymer Field, and flint and pottery scatter from fieldwalking. The area has a deeper history which we are exploring.

There are also interesting sites that post-date the town in lots of forms including deserted and shrunken medieval villages with visible hollow-ways around Bixley and Arminghall, a plethora of interesting Georgiana and Victorian buildings, farms and boundaries, some of which date back to Tudor or Medieval times and even earlier. There’s There are even modern sites of interest such as the remains of a Chain Home Low radar station including a surviving tower at Stoke Holy Cross, remnants of Second World War stop lines in the form of tank obstacles, pill boxes and Home Guard posts, plus a starfish site to drive Luftwaffe bombers away from Norwich, there’s even and cold war history in the form of OC sites and dugouts buried in the fields.

It is important to recognise that although Caistor Roman Project started with the Romans the site and history of the area is much deeper and exploring this gives us more context for it’s its development and subsequent decline.

The first survey and report were undertaken at Bergh Apton Manor in 2019. It is still in progress with interesting finds alluding to past activities from the late Georgian period, much of the property (excluding the buildings) has been surveyed, leaving the land associated with Bergh Apton Hall Barn to be completed soon. At some point a survey will be made of the buildings.

Bergh Apton landowners and locals have been eager to help CRP expand our network and we have been warmly welcomed by a number of interested and interesting people; there are currently over 20 properties in our portfolio and discussions are underway with owners about the project and approach. This has frequently involved a ’walk around’ properties, establishing the location of boundaries and to gain an initial understanding of the sites. The nature of the sites varies widely and includes working farms, some with medieval origins; a number of interesting metal and pottery finds have been recovered. Return trips to this area are planned.

An impressive rural estate with extensive land which has yielded interesting multi-period finds including a first-century Roman coin of Domitian, Georgian carriage furniture and horse harness and a really lovely Neolithic flint scraper. An interim report is in the process of being written and the finds are being recorded on the PAS database.

As a second stage of our methodology a preliminary survey incorporating metal detecting and collection of pottery scatters and worked flint is proving a very successful approach. Based on the survey results, further metal detecting and field walking of around 30 acres of arable land is planned. This will hopefully yield results on the use of the land and the depth of human occupation and use. Plans are in place in the future for field walking of a further five hundred acres or more.

Our field group will also survey two properties that have interesting arable land to survey in the next few months, including a field supposed to have a Roman road from Caistor St Edmund running across it. We have a clear methodology based on best practices from BAJR and Historic England which we are refining to meet the evolving needs of our research. Our aim is also to validate the oral and written histories of a particular parish using an archaeological approach.

Venta Icenorum: “doing different” in the land of the Iceni

A Roman town at Caistor St Edmund, Norfolk was abandoned after a few centuries and is often viewed as an urban failure. William Bowden finds a more compelling story

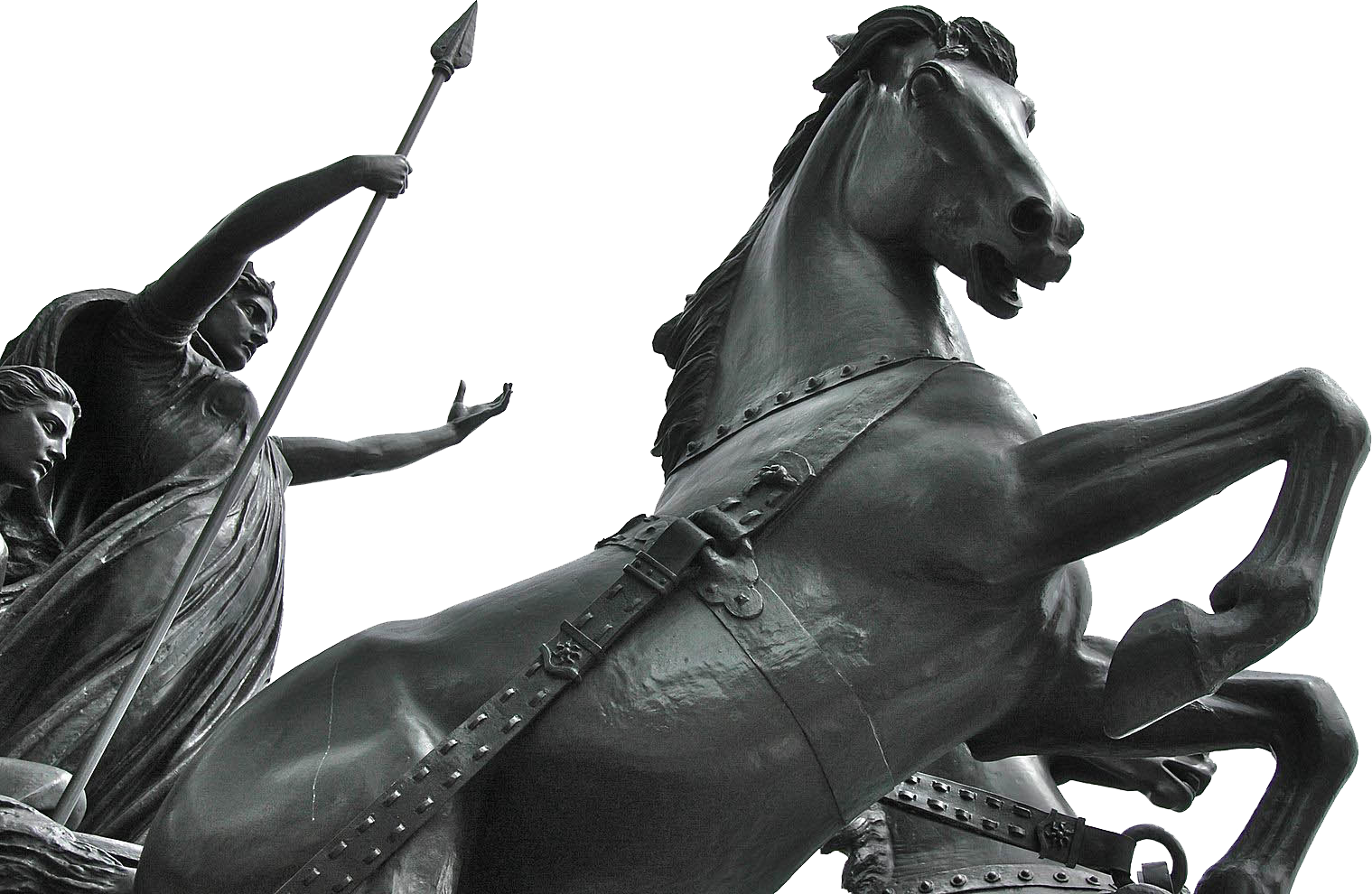

In Norfolk, according to the local saying, people “do different”. The county takes pride in residents like Boudica or the Singing Postman who followed their own path. The idea of difference as an expression of identity has also become important in the study of Roman Britain and the empire as a whole. The old homogenous Roman world of fora, amphitheatres, baths and wine has been replaced by myriad notions of empire, differing according to local circumstance and the viewpoints of those who experienced them.

In this new complex Roman empire, difference in dress or diet or anything else that manifests itself within the archaeological record takes on a new importance reflecting the expression of local identities within the new political realities, or resistance – implicit or explicit – to the control of Rome. Roman Britain, a small province on the distant fringes of empire, represents an ideal arena to explore such expressions of identity. The Roman empire that Britain encountered was not that of Rome and Latium, but instead an extraordinary melting pot of Italians, Thracians, Batavians and others, as soldiers, merchants, slaves and administrators, that found their way to the province in the decades following the invasion in AD43.

How did the land of the Iceni (comprising much of present-day East Anglia) respond to this changing situation? Venta Icenorum was the only major Roman town in the territory, and was its civitas capital. Traditionally seen as being founded in the aftermath of the Boudican rebellion in AD60 or 61, it has been viewed as small and impoverished, with a weakened local aristocracy lacking interest in the material and social attributes of Rome. The absence of mosaics and the small scale of its public buildings were something of a disappointment to its first excavator, Donald Atkinson, who described the Iceni as “achieving an imperfect degree of Romanisation”.

The idea that the town was something of a failure has been a frequent trope in the literature on Roman Britain. Since 2006, however, in collaboration with the Norfolk Archaeological Trust (the site owners) and the Caistor Roman Project community archaeology group, the University of Nottingham has carried out excavations and surveys around Venta Icenorum. The story we have uncovered is much more than one of simple success or failure.

Discovering Venta

The Roman town at Caistor St Edmund (slightly south of Norwich) first came to public attention in 1929, following the publication of an extraordinary aerial photograph. Taken during the dry summer of the previous year, it revealed the streets and buildings of the Roman town with stunning clarity as parchmarks in a crop of barley. The resulting interest led to Atkinson’s excavations of some of the buildings seen in the cropmarks, including the forum, the baths, two temples and the south gate. His interpretation of the site was formed fairly early in his campaigns (which ran until 1935), and he concluded that the town was laid out in the 70s following the “pacification” of the Iceni. The evidence for this interpretation was actually quite limited. Our excavations have suggested a more complex picture.

The town’s origins are obscure. Although the frequent discovery of iron age material in the region, particularly to the east, suggests a significant pre-Roman presence in the area, our excavations have detected little evidence of iron age activity in the area of the walled town itself. Another possible origin for the site lies in a post-Boudican military presence. Certainly evidence from coins and pottery suggests that there were people on the site after AD61. The geophysical survey, however, shows no sign of a military base beneath the later walled town. Thus far evidence for buildings before about 90 is almost non-existent.

An important aspect of earlier hypotheses of a military origin for the town was a defensive ditch system, seen on aerial photographs of areas to the south and east of the site, and previously interpreted as remains of a post-Boudican legionary camp. However, the National Mapping Programme, followed by our geophysical survey, identified further elements of these ditches to the north. This suggested that they were part of a large kite-shaped enclosure with a perimeter of over 2.3km, that was probably an early defence for the town.

Excavation of a section through these ditches in 2012 showed that they were of second-century date and were backfilled by 200. Things we found in these ditches, which included fragments of ceramic figurines and an inhumation burial, suggest that their function was symbolic as much as defensive: objects (and human remains) were placed in them for reasons that are now lost to us. More recent excavation at the northernmost point of the “kite” noted part of what seemed to be an articulated horse skeleton at the base of the inner ditch, reinforcing the impression of a symbolic purpose. Such “structured deposition” has also been noted in pits within the town itself.

Although these ditches enclosed an area of 35 hectares, streets and buildings in the early second century appear to have covered a considerably smaller area. Donald Atkinson argued that the streets were laid out in the 70s. All the evidence from the early excavations, however, supported by the present project suggests that the street grid only began to emerge in the early 100s; parts of it were not being formalised until the end of that century or later. Evidence for early settlement within the ditches is currently confined to the central area of the walled town, comprising clay and timber buildings, some decorated with painted wall plaster, possibly including a timber forum. Much of this early settlement seems to have been destroyed by fire in the mid second century: a conflagration is evidenced by the burnt remains of timber buildings we found beneath the later masonry forum in 2011, and by the remains of similar structures also destroyed by fire in the area north of the forum, discovered by Atkinson in 1929.

It seems therefore that our early town was a small nucleus of timber and clay buildings within the beginnings of a street grid, surrounded by a colossal circuit of ditches that enclose an area far bigger than the settlement itself. The reason for this disparity is not clear, but it could suggest that the ditches indicate an urban vision on a grand scale that was never realised. The centre of this settlement apparently burned down around AD150, but over the following 50 years we see the construction of new masonry buildings, in common with many other towns in Britain. These included a stone-built forum and basilica, temples, a bath-house and possibly a theatre. An amphitheatre, revealed to the south of the town by aerial photography, may also belong to this phase. The street grid gradually expanded but many parts of the town appear to have been quite sparsely occupied until the 200s.

Change and renewal

Civic life seems to have been fairly short-lived in Venta Icenorum. At some point during the third century, the forum seems to have been used as a rubbish dump. Excavations in the north and south wings revealed deposits apparently deriving from casual disposal of domestic waste. There is, however, no obvious sign of such abandonment in the forum basilica, suggesting that it continued to function as the administrative hub of the Icenian territory.

Probably in the later 200s, the town was surrounded by a new wall circuit, enclosing a much smaller area than the earlier ditches and leaving a number of streets outside the defences. The construction of the walls seems to mark a new period of dynamism in the town’s existence, as previously peripheral areas saw new and intensive activity during the fourth century. This included the construction of a major new building on the site of the earlier forum in the mid fourth century, apparently also incorporating the basilica.

What was this new building? Although it has been described as a forum, by the fourth century the concept of fora as centres of civic life, in which local elites participated in the machinery of government, was largely anachronistic in the western empire. It may instead have been a praetorium – the headquarters and residence of a military governor – reflecting the new fourth-century realities, in which military command and civil administration were increasingly intertwined. Certainly, Caistor appears to have gained a new strategic and political importance during the fourth century, reaching its apogee just as other towns in Britain and the western empire were shrinking. Some late Roman metalwork finds from the forum area and elsewhere in the walled town may also have a military association, although such items had a wide circulation as the lines between military and civilian identities became increasingly blurred in the late Roman world.

The fact that this once thriving settlement is now a quiet field inevitably evokes notions of decline and fall. However, although evidence of activity within the walled town is limited after the start of the fifth century, the surrounding area saw significant activity from the fifth to the eighth centuries. Early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, of which the earliest phases may be contemporary with the latest activity within the town, are known from the east and north-west. Dunston Field, across the river Tas to the west of the town (acquired by the Norfolk Archaeological Trust in 2011), saw the recovery of considerable numbers of middle Saxon coins, while the field was still under the plough, and aerial photograph evidence and geophysical survey suggested the presence of sunken-featured buildings. Subsequent excavation revealed a sunken-featured building dating to the seventh or early eighth century, and it now seems clear that there was an extensive middle Saxon settlement adjacent to the Roman town. The implication is that Caistor remained a place of political importance long after the nominal “end” of Roman Britain, perhaps until it was ultimately superseded by the rise of medieval Norwich.

Local difference

Parts of Britain were remarkably cosmopolitan during the Roman period. But only a small percentage of the population at any given time would have been born outside mainland Britain, even if some of those, such as the army, were highly visible. Most of the population of Venta was presumably of Icenian descent, and localised traits can perhaps be detected within the archaeological record. Consumption of olive oil, for example, was limited in comparison with other British towns, suggesting difference in food preparation among certain groups (although olive oil disappears generally from Britain during the third century). Burial practice too is intriguing. Evidence for iron age burial in the Iceni territory is very limited, suggesting mortuary practices that left relatively little trace in the archaeological record. The limited evidence for the dead continues into the Roman period suggesting the maintenance of such traditions. Little funerary evidence is known from Caistor, and the few burials that we have recovered are late Roman and demonstrate considerable variation.

Interpretation of the geophysics suggests that Caistor’s inhabitants also showed little obvious interest in the types of courtyard houses that we see at towns such as Wroxeter (near Shrewsbury), while the evidence of the early disuse of the forum suggests that civic life took an even more limited hold than it did elsewhere in Roman Britain. However, other new forms of material culture and behaviour were readily adopted. The evidence of coin use at the town, for example, is comparable to other urban centres, while the recovery of Samian inkwells, numerous styli and pottery bearing graffiti is indicative of widespread literacy.

The archaeology of Caistor thus suggests something more complex than a narrative of resistance or Romanisation. Instead we see a town whose inhabitants used new materials and social mores to their own ends at the same time as their lives were shaped by wider cultural and political forces over the long arc of the town’s history.

William Bowden is professor in Roman archaeology at the University of Nottingham and a trustee of Caistor Roman Project. Survey, excavation and post-excavation work at Caistor were generously supported in particular by the British Academy.